Eye Contact

Over-rated & Over-usedWhen beginning your journey in wildlife photography, one of the first rules you learn is along the lines of,

"make eye contact",

or,

"the eyes must be the center of attention",

or,

"without eye contact, your images will never be powerful"

...or something like that.

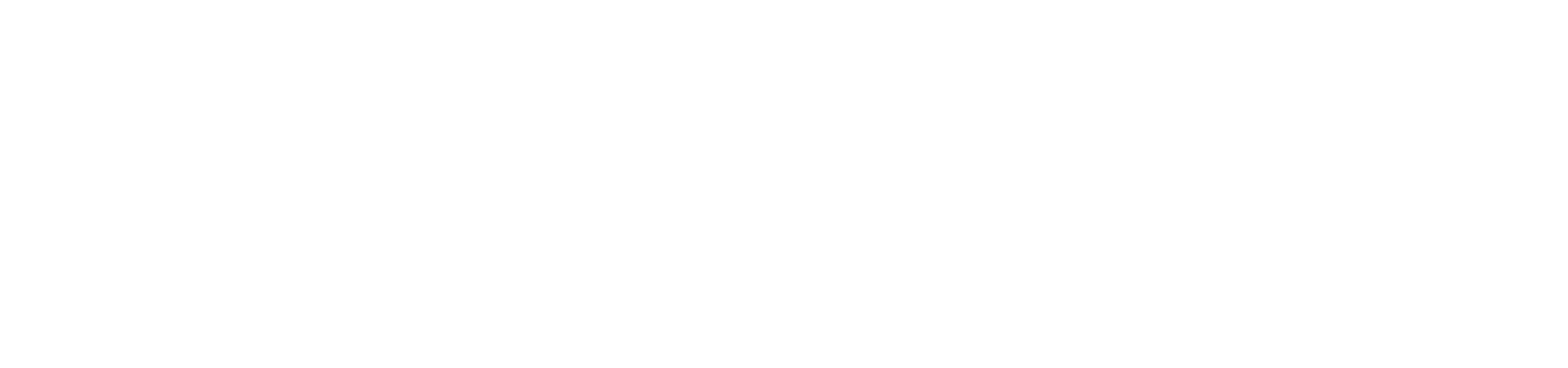

Are you going to kill & eat me?

Seems logical. The human psyche is heavily invested in visual cues, with eye contact being way up there on the list.

For example, when meeting someone for the first time, if they look down, away or just won't make eye contact, what's your first impression? Shy? Maybe. Furtive? Probably. It would be easy to form a negative impression of a person just by the lack of eye contact. I'm fairly certain that 99% of people would form, even if only subconsciously, a negative impression.

When we look at a photo of an animal, if the eye contact is strong, then we have a strong connection with the image. If you see a portrait of a mature male lion which is staring directly into the lens, into your psyche, there's a powerful emotional response. Tingles of fear, acknowledging the animal's power, a primal response to a predator.

Or, if it's a cute mammal, we go all gooey looking into those large soulful eyes.

Admit it, I'm adorable

So when we first hear of this "rule", we immediately react positively to that direction, because it's very much part of our human nature. We know, even before we take our next shot, if the animal is staring into the lens it will elicit a strong response from our audience, and ourselves. It's logical. It's obvious. It's human nature. It's a golden rule.

But take a step back for a minute.

What happens if, for example, you come in close contact with a primate, such as a gorilla in the mountains of Malawi, or a snow monkey in a mountain onsen in Japan or some chimps in a rescue center?

If you move close and look deep into their eyes, what will happen?

Don't try this, because if you do, you'll have your face torn off. You'll quickly realise that primates take direct eye contact as a challenge, a threat, an attack.

I'm going to tear your face off

And not just primates. Staring into an animal's eyes, pretty much across the board of most animal species, will elicit a negative response. Our relatively flat faces with forward pointing eyes scream "predator!!!!" to animals and birds.

Staring at an animal will have them either flee from you, having received a threat via your direct gaze, or have them attack in response to your perceived threat.

Do you think that staring into the eyes of a grizzly bear will make it your friend? No, it won't. But it will, possibly, make you their next snack.

So how does this relate to the "rule" that all wildlife photos must have strong eye contact? After all, it does contribute to a strong emotional reaction in your audience.

Here we need to take a sideways step, and one backwards too, and examine what you want out of your wildlife photography. Let's engage our brains instead of just jumping in and doing what's popular.

When we take a more holistic approach to our photographic endeavours, we need to consider more than the immediate knee jerk reaction of populism.

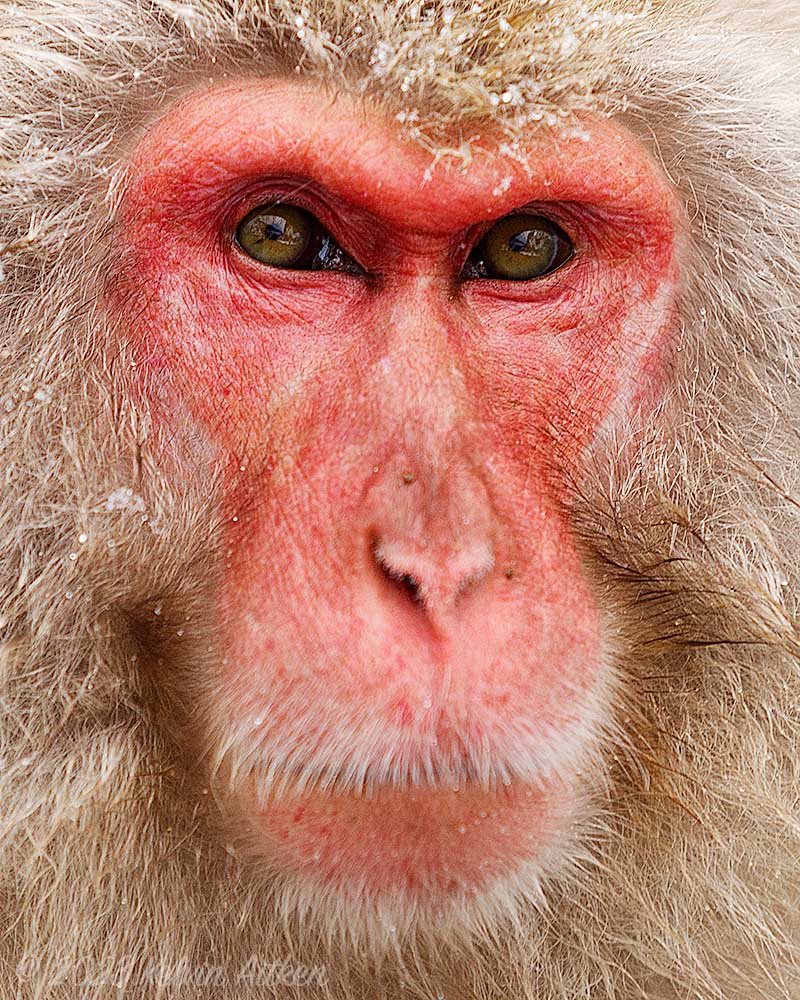

Social media, for instance, imparts tremendous pressure on users and viewers to appeal to what's "popular". In other words, if a photo receives a huge number of "likes", it's considered "good". You've succeeded.

Pressure to perform, at a price

You get more followers, you get more social acknowledgement, you get lots of positive comments, your endorphins soar, you feel good. You may even begin to be courted by commercial suppliers who want you to push their products, either for "freebees" or payment.

A side product of that pressure is increased image output to keep that endorphin rush going. That means posting every day, or something along those lines.

A very active, talented wildlife photographer will get between 1-3 great shots per year. Or none in a bad year. They will also get 100 or so "good" images. The rest really should stay out of sight.

To conform to peer/industry pressure, your average photographer will be forced to post sub-standard work, just to keep up. Most of those sub-standard images will have the subject staring into the lens, giving it that extra bump to get it over the hump of banality. Yes, a sub-standard image will get lots of likes if the subject is staring into the camera.

Is it a cheat? Ah, sort of, dunno, maybe, who cares. The point is this:

Are you content with praise from others or do you want more than that, to have YOUR OWN approval? Do you want to make better images every year? Do you want to look at an image (those 1-3 per year that are on a different level) and have that deep feeling of contentment, of accomplisment? If so, start exploring image construction that isn't the easy way out.

Push yourself.

I'm sure you've seen it, a portfolio of work on a social media platform that's entirely shot to formula. e.g. Small bird against super soft out of focus background. The shots may look good, but great? Not really. Easy? Yes. Lots of applauding, back slapping and "likes"? Yes. Different? Not a chance. World class, head and shoulders above the rest? No. Deeply satisfying on a personal level? Probably not, if you want more than just approval from a faceless audience by posting formula pics.

Same goes for photo competitions and selling your work in general. The pressure to conform to the norm is huge. Going out on a limb, ignoring the formula, is a big risk.

H. L. Mencken (1880-1956) said something along the lines of, "nobody ever went broke underestimating the intelligence of the average citizen".

If you want the quick "feel good" experience provided by social media, then go for it. It's not a major sin. Everyone's doing it. You'll be quite popular with the average citizen for that 2-3 second viewing period.

Yolo. I have no regrats

But if you want to actually grow, have your photography drag itself out of the steaming pit toilet of social media and populism, consider your subject.

If the animal is staring directly into your camera, at you, at your presence, then you're definitely impacting the animal in a negative way.

Why?

Because it's trying to decide if you're a threat, or maybe a meal. Your presence is changing the behaviour of the animal.

Sometimes, that's not a big problem. Sometimes it's just curiosity. Sometimes the animal sees your movement and briefly checks to ensure that all is well, then it gets on with its day. Sometimes it's accidental or unavoidable or your presence is of little concern to the animal. Sometimes, that's all you get, a flurry of movement, camera swings up, critter pops out to see if you're a threat, camera fires, critter takes off. One shot of a staring critter, and a few of its butt as it runs away.

But other times, the negative impact of your stare is so great you may as well walk up to it and hit it over the head with a baseball bat.

Then other times, the animal sees you and decides that you're its next meal.

Having an animal stare directly into your lens is a lazy way out of a creative situation. Taking such a shot isn't necessarily a bad thing, but it can turn into a crutch if that's all we aim for. We don't take our photography to the next level, to do something more than the obvious.

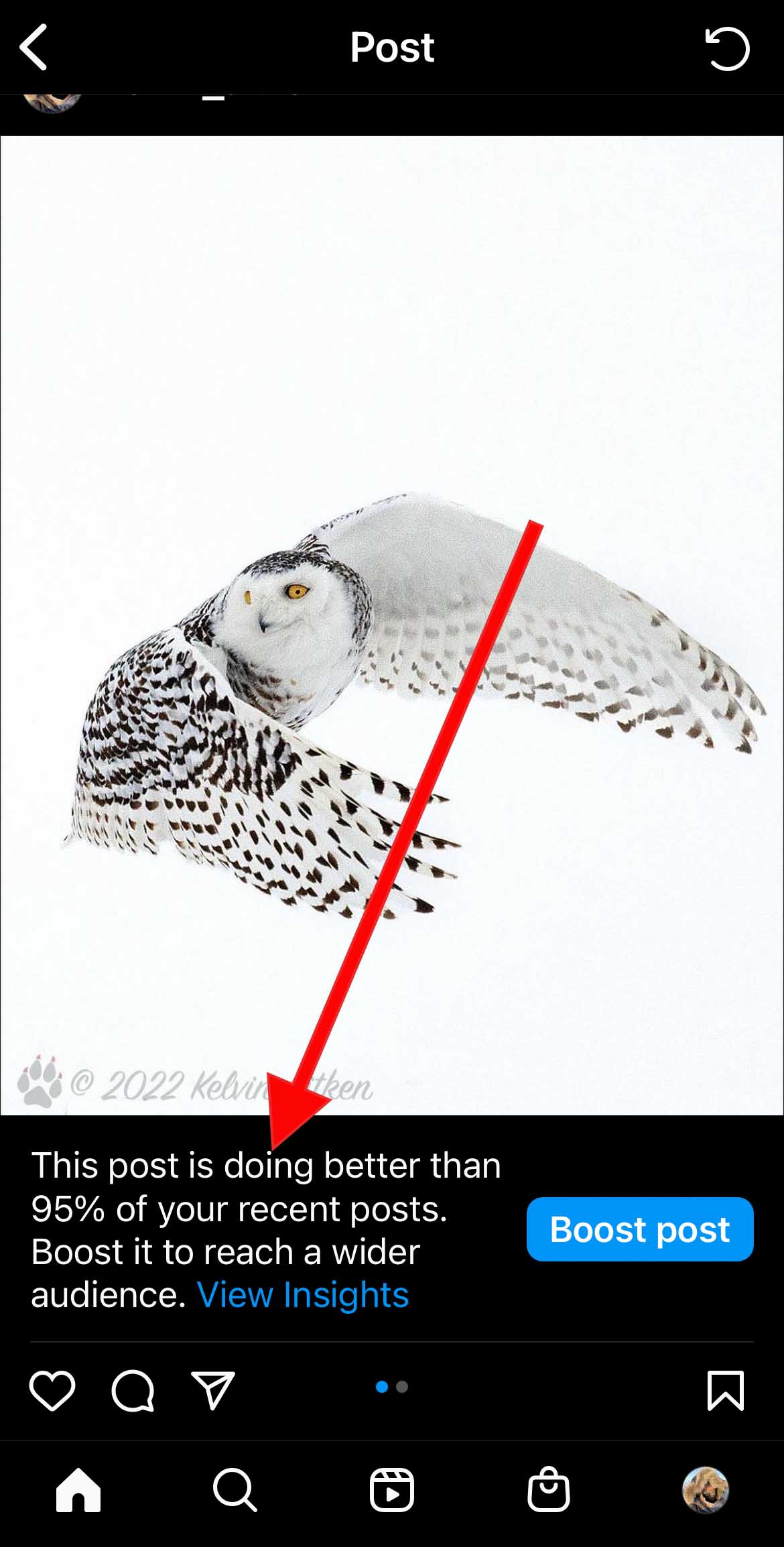

Instead of, or as well as, taking the "staring into the camera" shot, try shooting an image where you, or the viewer, are not the center of the universe. Look for images that still shows the eye (or not at all, those shots work too) in a way to suggest that the animal is not about to fly into a rage or frozen in terror, ready to blast off in full escape mode.

I think I hear a vole over there...

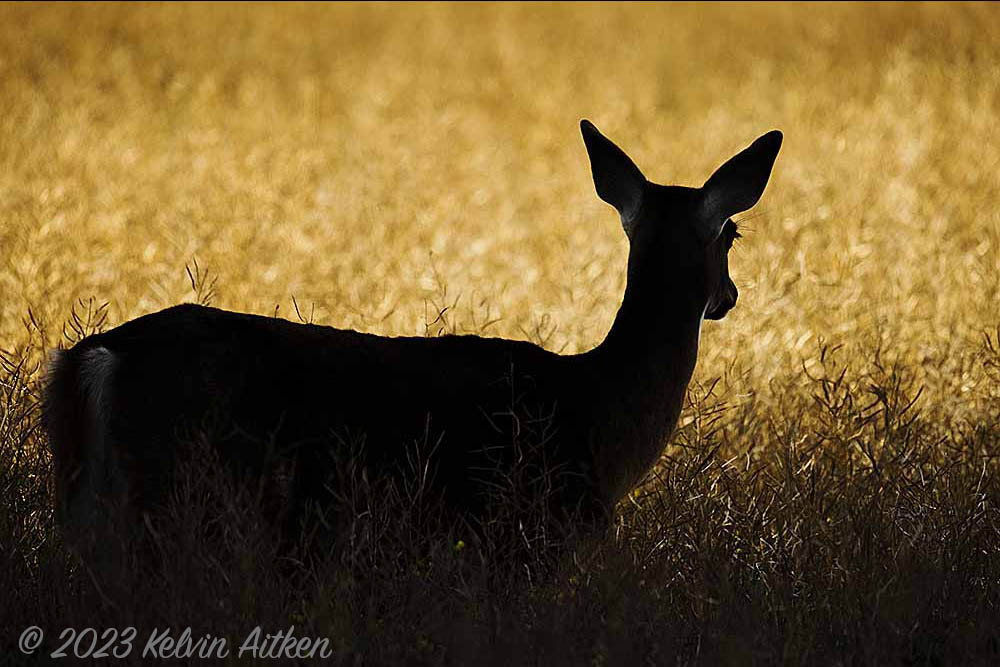

Images without direct "staring into the camera" eye contact convey the message that we, the viewers, are watching an animal while unobserved, seeing it in it's natural environment, behaving naturally without fear or predatory intent. It opens up a new window, a new view or perspective on the animal.

We're no longer the center of the universe.

The effect on the viewer is subtle but powerful. Suddenly, the gaze and focus of the animal is no longer on them. Subconciously, there's a mental shift. Since you're no longer the center of attention, your mind no longer sits in the default "most important person in the room" position. It has space to move, able to shift from the default to a broader context.

Have you ever seen a person approaching you and you looked them in the eye, or at their face, either deliberately or accidently? Of course you have. It's human nature. Then, have you had that person deliberately break that brief eye contact by blinking and looking away?

Of course you have. We all have. We're human. There's a 100% certainty that we've broken eye contact in just the same way, many times, either with deliberation or by subconcious reaction. We're busy or stressed and we don't need the effort required for social interaction.

That breaking of eye contact can be brutal. It can be like a slap across the face. Or you might even feel a sense of relief. You really didn't want anything to do with that person, you were just responding to a new face like any other human.

When you see a photograph of an animal staring into the lens, your human nature locks on, not blinking and looking away to break that connection. It's a strong bond. Powerful. Simplistic. Basic.

It locks you in and destroys any other view or insight. It captures your audience, locks in their base instincts and provides that cheap thrill of connection.

It works very well. Impressivley so. Boring, shallow, same 'ol same 'ol images get a free pass. And most probably a lot of likes and comments.

You win, if that's your game. But at the same time, you lose so much.

One holds you prisoner, the other lets you roam.

Do you like chocolate? Or ice cream? Most people do.

But if that's all you eat, you will never experience the exotic taste of oysters opened fresh off the rocks, the sweet sensuous taste of a ripe mango or the bitter tang of lemon. Or any other food you would like to name.

Just serving up "staring into your eyes" images might be an easy, simplistic and popular dish, but it will leave you starving for fulfillment.

When you break that puerile visual trope, your audience is no longer restricted to thinking, "Oh, that's a nice photo of *insert name of animal here*". They are now free to explore the possibilities.

They being ot ask, "What's the *insert name of animal here* doing?"

What's it looking at? What's it thinking? Is it hunting? Looking for prey? What sort of prey? Or looking for a predator. What sort of predator? What is it outside the frame that it's focused on? What will it do next? What has it just finished doing? All sorts of possibilities arise.

A relaxed animal is a happy animal, which will lead to natural behaviour

Then there's also the thorny issue of ethics. Ooooooh, here we go. The deep dive.

We aren't aliens. We all, animals & humans alike, belong on planet earth. We are endemic to this planet. We have just as much right to go outside and wander about as any animal. We share the planet.

That said, we have a moral obligation to ensure that our actions do not unfairly impact other species. As wildlife photographers, that's entirely understandable. Without animals, we would be pursuing far less enjoyable endeavours such as street photography or football.

So at the very least, as wildlife photographers we need to endeavour, even if only imperfectly, to enable our subjects to live their lives normally. We are trophy hunters, but we get to go back the next day and gather the same trophies, or have others get the same trophy. The animal should not have an end of life experience over a photo that will probably be scrolled over in 2 seconds then forgotten.

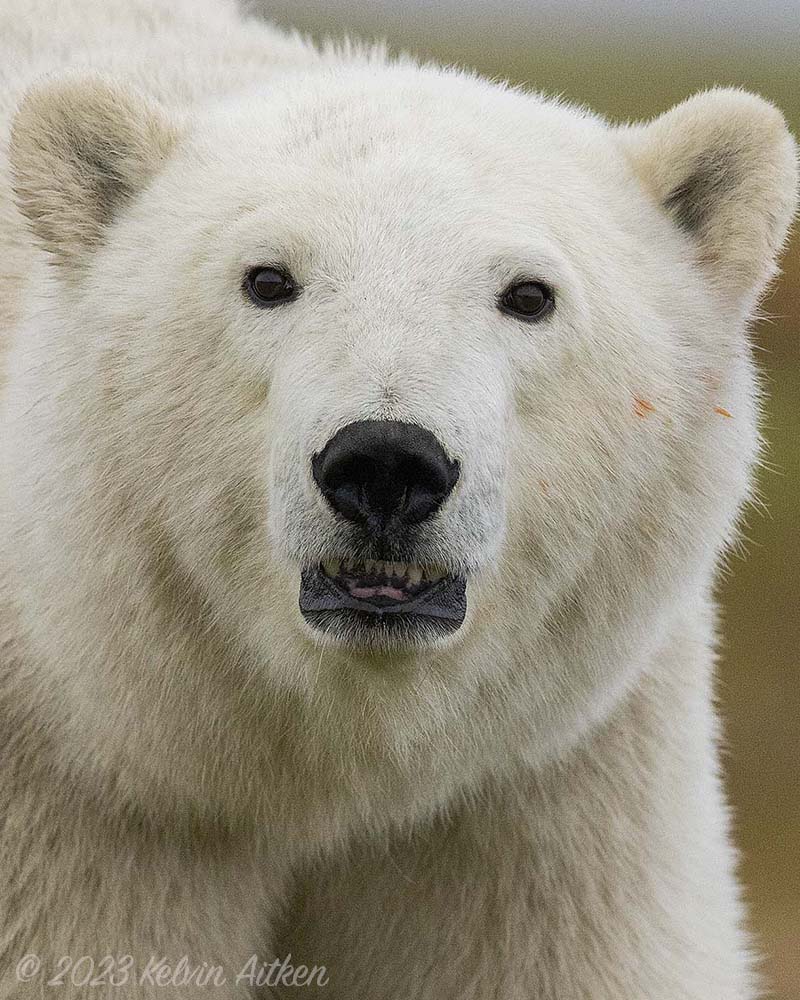

You don't always need eye contact

And this is the issue with "staring at the camera" pics. If we are interrupting an animal from feeding, or breeding, or making it vulnerable to predators, we're causing harm to that animal, even if only superficially. If we strive to interrupt every single animal we encounter in order to have it to stare into our camera, that's not a good look (pun intended).

That's why national parks have rules about contact with animals. Chasing them, cornering them, baiting, calling or in other ways harassing an animal to get a shot is frowned on and, in most cases, illegal. Who hasn't seen a video of some idiot chasing a bison with a phone camera.

That's why photos of birds on the nest are banned in reputable photo competitions. Why? Because there's a good chance that, by taking those images, you place so much stress on the adult birds that they abandon the nest. Eggs die from the lack of warmth, hatchlings starve to death or die of hypothermia or predation.

If every single image we take of an animal has them staring at the lens, maybe we need to adjust our approach a little. Or, even better, don't approach, let them come to you. Use a blind, be prepared to sit still for long periods of time, get up before dawn, stay until after dark. Capture the real animal, not just one staring at you hoping you won't kill it.

Make the effort to avoid the cliche. You'll thank yourself later.

I wonder what Clive's doing today...