Extreme Cold #1

Using camera gear in the fieldAs you may deduce from the title, this is the first article on dealing with extreme cold as a wildlife photographer.

So, to get this into perspective, let's define "extreme cold".

No, it's not zero Celsius, the freezing point of water. That's not extreme.

An inuit guide with a sun dog, which only appears below -30C in extreme cold

Well, it may be if you've lived all your life in the tropics.

I once boarded a bus in tropical Fiji that catered to the locals, not tourists. There was no glass in the windows, which for me was a life saver, as the air was hot and humid.

But for the locals it was winter. There I was in shorts and T-shirt, already starting to sweat it up. However, next to me sat a mother with a baby on her lap. The year old baby was wearing thick clothing and a woollen cap tugged down over her tiny ears. She was all decked out for the "cold".

Then there's the famous scene in Cool Runnings, a movie based on the Jamaican 1988 Olympic bobsled team when they are exiting the airport into the "brisk" winter weather in Canada.

The coach, played by John Candy, is used to the weather. He's expecting it and is only wearing a light coat. Not so the jamaicans...

So when I talk about "extreme cold" and wildlife photography, I'm not talking about a rainy day in London, I'm referring to temperatures below -15C at a minimum. It's not unusual to be out shooting in -20, -30 and -40 or more in the northern hemisphere. In the southern hemisphere you would generally need to be in Antarctica to experience those temperatures.

In fact, the lowest temperature ever recorded on earth was -89.2°C in Vostok, Antarctica. But we're never going to be taking photos in those extremes because no equipment of any kind would work. -40 is bad enough.

With that settled, let's look at keeping your camera equipment running in extreme cold while we're out looking for wildlife.

First off, you won't need to worry about your lenses, cameras and any other hardware. They'll work just fine in extreme cold.

In fact, you're far better off leaving your gear outside in a camera bag or any other type of sealed container (to prevent any snow being blown into the lens or any gaps in your camera body). You do that to avoid any issues with condensation, because, after all, condensation is just water in a liquid form, like rain, mist or fog. Nasty stuff, unlike water in a solid form such as ice or snow.

Just be sure to take the batteries and memory cards with you, placing them in a sealed plastic bag to avoid condensation.

Remember, we're talking about extreme cold so you never have to worry about rain or mist. You won't need a lens/camera cover at all unless you're shooting in high winds with a lens that's not weather sealed.

If you're worried about sleet or melting snow, then you're not working in extreme cold.

If you take your gear into a heated room, then you will have a problem with water and condensation. You're better off to just leave it all outside.

However, if, for some reason, you must take it inside, put everything into your camera backpack/bag or a large plastic bag (e.g. a garbage bag) and don't open it until it's warmed up to room temperature. That will eliminate any condensation forming on the cold metal and plastic of your camera gear.

Don't forget that you need to allow enough time for the warming process. This includes internal air spaces such as battery and card slots.

Keep a blower brush and cleaning cloth with you and that should allow you to deal with any ice/snow flakes the get onto your front element or eyepiece when out in the field.

The big problem, as you may have guessed, are your batteries.

Battery Charging

Let's start with charging batteries in extreme cold.

Any battery, in any equipment, is the weak point in extreme cold

If you're charging batteries in a heated room, such as a hotel or even in your heated car, then you won't have any problems, as long as you allow them to come to room temperature without attracting condensation, as mentioned above.

The problem with batteries is that they're very temperature sensitive. Extreme cold will drastically reduce the amount of time they can be used in your camera, but they also won't accept a charge if they're too cold.

Camera batteries are generally rated to work between 0-45C, so the camera manufacturers have no real interest in helping you when you're chasing a polar bear.

This also means that the battery's internal temperature needs to be up around 0C or more for them to efficiantly accept an electrical charge.

There are various ways to make that happen.

If you're charging from a power bank but you're in a tent out on the sea ice, or similar, then put the entire contraption inside your coat to allow your body heat to keep the batteries at a workable temperature. The closer they are to your base layer, the warmer their surroundings will be, so the further inside your layer system they are, the faster and more efficient the recharge.

That will ensure that they not only accept the charge but they will also fully charge.

I have also put the battery bank, charger, cable and battery rig into my sleeping bag, usually inside one of my down booties to stop them from getting dislodged by my nocturnal tossing and turning. Warm up the batteries enough to get them charging, go to sleep and wake to a pair of fully charged batteries.

Another system I use is where I take a small drink cooler, one that will take a six-pack of cans, into which I drop a body heat pack or a half dozen toe and/or hand warmers. Lay your powerbank on top of the heat pads followed by your batteries in their charger.

A reuseable alternative is to put hot/boiling water into a small (500ml) Nalgene bottle (they can take boiling water, a normal water bottle won't), place that inside a ziplock bag (one without any holes) in case of a leak, zip seal it closed and put that into the cooler.

Super secret charging weapon - Nalgene in a cooler. Don't tell anyone.

This sized cooler & setup can take two large powerbanks charging 8 batteries.

Be aware that a Nalgene bottle filled with boiling water can be dangerously hot. I usually put the bottle, in its ziplock bag, inside a thick sock to protect the powerbank and batteries with which the bottle is in contact. It also protects you from a burn plus, as a bonus, dries out your sock.

Check that the LED's are blinking, indicating that charging is happening, and close the lid. Place the cooler on something that will insulate it, at least a little, from the cold ground. The reusable heat pads, or Nalgene bottle, will provide warmth to rise up through the battery bank then up through your charging batteries, maintaining the interanl temperature of the cooler above 0C, enough to allow a full charge. If you're fussy you can even include a thermometer which can be read from outside the cooler.

In the morning your batteries will be fully charged, although seemingly dead or part charged due to the drop in temperature as the heating pads expired. While you have your morning wake up coffee, put the batteries in an inside pocket, as close to your body as possible, to allow them to warm up. They will be ready to use, fully charged, when you find your first subject later in the morning.

WARNING: Nalgene bottles with boiling water have been know to burst due to structural weakness (e.g. hairline cracks or damaged thread) so check them carefully before using them as heaters and always ziplock bag them for extra safety. Click here to see a video that shows how to make "bottle heaters" a lot safer.

Use any disposable heat pack to warm up your charging system

You can also use rechargeable hand warmers as well as, or instead of, the disposable warming packets. Just make sure that they turn on properly, as they also contain, and rely on, rechargable batteries.

The cooler doesn't have to be hot inside, just warm enough to keep the whole shebang around 0C or warmer.

If the batteries aren't charging, hold them in your hands or inside your clothing until they warm up enough to work again. It doesn't take much, just a minute or so in your bare hands is usually enough, or a couple of minutes inside your coat, a layer or two in.

Hot tip: if you need to warm up your hands or batteries or something similar, your groin is your best heat provider. Shove them down your pants and wait for the magic to happen. It's also a good excuse if the police catch you in a compromising situation.

You can also use your stove to create a warm area to get your charging done. Just be sure to avoid steam and moisture from cooking, for obvious reasons, and also don't catch anything on fire. The possibilities of an accident are a lot higher than using a cooler or sleeping bag, which is why I never use the stove.

The bottom line is that to ensure your batteries charge, and also reach maximum charge, you need to keep them at 0C or higher for however long it takes to complete the charging cycle.

Battery Use

Normally you would start your day, I hope, with a formatted card in the camera plus one (or two if using an accessory battery grip) fully charged batteries.

But in extreme cold, that won't work too well. Why? Because it may take a number of hours to find your first subject. In that time your batteries efficiency is being reduced by the sub zero temperatures.

-40C. When I put batteries in, the camera made a squealing noise, but it still worked

The last thing you want is to frame up your polar bear chasing a musk ox or pulling a seal out of it's breathing hole only to find that your batteries are flat. The cold will do that.

Similar to charging, if your batteries reach a low enough temperature, which is very easy in extreme cold, then not only will they not charge but they also won't deliver power.

The simple solution is to warm up the batteries. Unfortunately, that won't help if you only have a few seconds to get a shot before the polar bear runs off.

The fix for this issue is to keep the batteries warm inside your coat, and maybe even a couple of layers in, then put them in the camera immediately before you need them.

Sure, that takes time, but so does finding that the batteries you put in the camera hours earlier are now flat, removing them and replacing with warm batteries. So short circuit the pain and keep the batteries warm inside your coat.

An alternative that will keep your camera powered all day is to have a dummy battery in your camera connected to either a power bank or a tray holding your camera batteries inside your coat. The downside to this is that you're stuck with a cable between you and your camera, which will get in the way and possibly freeze stiff and break (if you don't have a cable made of the right material).

This sounds simple and it does work, but the type of dummy battery, connections, battery bank and battery tray (sometimes called a sled) all need to work properly with your camera. Back in the bad old days this system was cheap, easy and simple. But with modern cameras, especially mirrorless, you need to be sure that everything works properly, providing the right current.

There are commercial systems available or, if you know what you're doing, you can make your own. You just need to know what you're doing so that you don't fry your expensive camera and that the system provides the exact power that your camera needs. Cavet emptor.

To avoid all that, carry at least 4 or more batteries, or pairs of batteries if you're using a dual battery grip, to keep your gear powered all day.

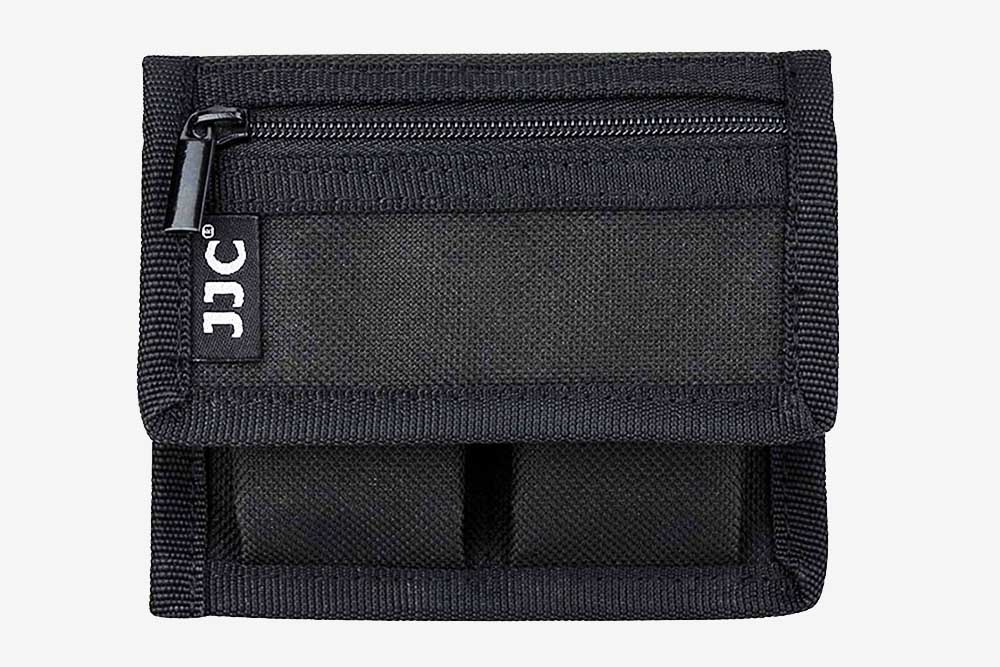

A nifty pouch to hold a pair of batteries plus a zippered pocked for memory cards

When you put your comparatively warm batteries into your camera, expect greatly reduced battery life. Normally you might get thousands of shots from freshly charged battery(s) but in the cold that will not be the case.

You can extend the battery life by keeping your camera up around 0C when not using it but even then, expect to be switching batteries regularly. The good news is that once you warm up your "dead" batteries they will recover their charge to some extent, so cycling them will help.

Also, especially when shooting video, heat generated by your camera will help your batteries to keep going, but keep an eye on the battery level to avoid missing shots.

For dead batteries in the field I carry a power bank and small, compact charger. Then, when things are quiet I can plug in a pair of dead batteries and have them charge up while stored inside my coat, or pants for that matter. These are the sacrifices we make.

I've always said that any task done in extreme cold is four times as difficult. That means it takes 4x the effort, time and concentration to perform a simple task, such as switching batteries and putting the dead ones on charge. Expect to expend a lot more time and energy doing simple, basic stuff.

Recent camera models have adopted the USB-C system, often ditching the old style micro port in the process. This negates the dummy battery system and is a huge step up in powering your camera.

New USB-C ports, shown on Olympus & Nikon bodies, are changing how we can use external power

All you need is a simple, but good quality, USB-C to USB-C cable. My camera came with a good quality USB-C cable but I opted for a Ugreen cable with a right angle connection to provide a more streamlined, less "knockable" connection.

Plug one end into your camera's USB-C port and the other into a powerbank. All done.

OK, there are some fiddly points that need to be taken into account. Most importantly, and obviously, your powerbank needs to have a USB-C port. That old powerbank you have sitting in the back of your cupboard won't do.

Also, the powerbank must be capable of "Power Delivery", usually having the letters "PD" somewhere in it's description and specs. Yes, old non PD powerbanks also "deliver power", but not in the same way as a PD powerbank.

The higher delivery capacity of a PD powerbank will let you not only recharge your camera batteries and phone, but also a laptop and, most importantly, your camera.

The powerbank rating should exceed 3A at 9V or 30 watts (3x9=27, rounding up to 30W). Your average mirrorless camera will need at least that to be able to start up and run.

I'm currently using an Anker PowerCore+ 26800mAh PD 45W powerbank which not only runs the camera but can also charge my Macbook Air M1, plus all the other operations such as powering one or two twin battery chargers, recharging headlamps, air bed pump, tent lamps, etc. The brand is not important, the PD rating is what you need to check plus the wattage as mentioned.

The powerbank is put into an internal pocket inside your coat (or under additional layers), keeping it warm and operational, with the USB-C cable running to the camera. If I need to leave the camera for a while I can just unplug the cable and walk away. No need to fiddle with cable junctions or dummy battery removal.

However, there's one major problem with this simple cable connection. It doesn't work in extreme cold. Cool weather, yes. Cold weather, yes. But extreme cold? No.

Why?

The weak link here is the camera's batteries that need to be in the camera for this system to work. The external battery will charge your internal batteries and also power the camera, but it needs those small batteries in place. And that's the problem.

We know that your camera batteries don't last very long at all in extreme cold. Also, we know that in order to accept power from a charger (in this case, our external PD powerbank all warm and toasty inside your coat) they need to be relatively warm (around zero degrees).

So if the camera batteries are in extreme cold they won't accept a charge. Therefore, the whole system fails. After a short time, maybe just a few minutes, they're dead and not recharging, no matter how good our external battery may be.

What this means is that while you need an external battery in extreme cold, staying relatively warm inside your coat, the only way it will work is by removing the camera batteries and repalcing them with a dummy battery.

As mentioned earlier, dummy batteries do work, but modern cameras are super finicky. There are all sorts of issues that need to be accounted for, and I'm not going into that extensive subject here. But, suffice to say, your dummy battery needs to be specifically designed to work in your particular camera body.

With a good quality dummy battery installed, one designed to work with your camera model, the whole extreme cold issue is resolved, because you now have an external battery that doesn't rely on your internal camera batteries at all.

With the camera batteries removed, an external PD powerbank, acting through a dummy battery, works

A final word here: test your system in extreme cold before you use this on an expensive trip. There may be issues that need to be solved and doing so while a pack of arctic wolves take down a musk ox is not the time.

For example, while I have a good quality dummy battery with a built in chip to mimic a genuine battery, my camera still detects this, so when I connect it all up and turn on the camera, it asks me if I'm using a conterfiet battery. Not something you want to be fiddling with when the wolves strike. I go through a couple of screens to reassure the camera that all's well and from then on, the camera works fine, even when waking from sleep and also when I turn the camera on after being turned off.

If I remove the dummy battery, I need to go through the "reassurance" process again, but at least I know it's only for the inital startup and I won't have to repeat it as long as I leave it all connected. So, something I would do each morning before heading out.

This system works, with or without an accessory battery grip. To avoid issues, remove any additional camera batteries that may be in the tray. Some cameras have a single large battery inside a built in battery grip so be sure to buy a dummy battery designed to work with your particular camera model.

REMEMBER: your system will probably work differently. Some better, some worse. So test, test, test. But do so in the temperatues in which you will be working. If that means arriving a day early on your trip, do it. Camera gear probably isn't the only thing you will need to check. Tripod operation, LCD functionality, gloves, clothing, footware, foot and hand warmers, etc all need to be tested in working temperatures, so if it's not cold enough at home, get to your destination early, or at leas schedule some prep time.

Can everyone please stop. My camera has a battery problem...

WARNING: Don't assume that my system will work with your camera. The setup is simple, but do your own research and check to see what system will work with your camera model. I can't help you if you fry your camera because you chose the wrong product(s).

Lenses & The Fuzzy Issue

People are always asking me, "Why are my photos, taken in winter, not sharp?".

Well, actually, they never ask me that, but they do ask a lot of other people, you know, influencers and such, and pretty much never get the right answer.

The answer is simple: heat haze.

OK, "heat haze" is not really logical or accurate. The issue is when two layers of air, or water for that matter, have different temperatures. At the point where the two layers mix, you get a fuzzy, blurring affect as the difference in temperature also means differences in density and, therefore, differences in how light is trasmitted.

In fact, it's purely a matter of density difference, as you can get the same effect from mixing two liquids of different densities but the same temperature. Temperature just happens to be one factor that changes density of a liquid or gas, which is why two layers of air or water with different densities cause the wavey visual effect we call "heat haze".

Light travels differently in a layer of air that's at one temperature versus another layer that's warmer or colder. You don't notice the difference until you have them mix.

If you're in a hot desert, the temperature difference between the air lying on the ground (usually regulated by the ground's temperature) and upper layers of air heated by the sun, you get a very obvious shimmer. Unless you're looking to record that effect, it destroys image making, both stills and video.

But the same can, and does, happen in extreme cold. As mentioned above, it's not the temperature that's the issue, it's density variations caused by temperature variations.

So air laying on the ground (or snow or ice) has its temperature regulated by the average temperature of that ground. But air above that layer has its temperature regulated by the atmosphere, most notibly by the sun. If they're different, you will get "heat haze".

Now imagine you're in a car on a -30C day with no heat haze. Your seat warmers are on, steering wheel heater on, heater blasting warm air into the cabin and at your feet. Suddenly you see a moose come out of a clump of trees. You slam on the brakes, wind down the window and grab your camera. Focus locks, exposure set and you blast away.

But every picture is soft, fuzzy. It's in focus, you can see that. There's no subject movement and your camera was steady.

Why? It's the same heat haze issue. When you wound down your window you suddenly had a wall of hot/warm air hitting a wall of cold air. The temperature difference has the two layers mixing, causing the heat haze where the two densities mix, and there you were taking photos with a blurry filter in front of your lens.

Also, if you got out of your car and walked a couple of meters away, you still have warm air stuck inside your lens hood. Air is surprisingly "sticky", so even if you were to take off your lens hood you will still have warm air clinging to your front element. Maybe not a lot, but it's there.

The coyote's in focus but I may as well shoot through a coke bottle

The Fuzzy Fix

The solution is simple: avoid the temperature difference by either avoiding it all together or allowing enough time to stabilise the air in front of your lens with the surrounding cooler air.

Allowing time may mean waiting 10 minutes, but who wants to do that. Take off your lens hood, flap it about a couple of times to replace the air inside (remember, air is kinda sticky), wave your lens around a bit to wipe off that last bit of warm air clinging to the front element, replace the hood and you should be good to go.

The temperature of the air/gas inside your lens and camera has zero effect on this issue. It's where the two air masses mix that causes the blurring and your gear is pretty will sealed. If your front element is comparitively hot, maybe from having your heater blast hot air on it for the last hour, that can warm the air touching the front element, which may have a slight effect, but glass cools rapidly and the amount of air affected is minimal, especially compared to a wall of hot air exiting your car window, or your lens hood full of hot air.

You can also just wave the lens about a bit, especially if your lens hood is short, or, as I often do, drive along with the window cracked and the lens pointed in a way to have the outside air flush out the warm air. That can cause issues with snow and ice crystals getting on your front element though, so use with caution.

But the easiest, guaranteed and certain way to avoid the issue in the first place is to (brace yourself) TURN OFF THE HEATER AND CRACK A WINDOW!!!

Yes, keeping the interior of your car as close as possible to the outside temperature will solve the issue 100%.

Yes, it will mean wearing your full extreme cold clothing layers, including boots, gloves, mitts and face protection, but your shots will be sharp.

Sure, it's uncomfortable and generally unpleasant, but you're not out for a joyride. You're a wildlife photographer and being uncomfortable is a bonus, especially when you're back home in your heated house and up comes your pics on the computer all crispy sharp and lookin' good. Your discomfort is forgotten, overwhelmed by your gold medal shots of a moose crowned with snow.

But your peers, who opted for comfort and drove around all day in a heated car, have wasted the opportunity and have zero useable results.

Sucks to be them, right?

The same principle applies in hot weather, or any weather for that matter. If your car is cooler than the outside summer heat, you're going to have the same issue. Prepare to be hot and uncomfortable or accept the fact that you can't "run and gun". You have to allow time to clear the air in front of your lens.

Cameras In The Cold

While your camera should work in -40C, it will start to struggle as it gets colder. The first thing to lag at around 0C will be your rear LCD screen along with the small top screen that displays your exposure data. Using a modern phone in extreme cold will quickly show you how quickly an LCD screen will spit the dummy.

Fake screen & thumb drop shadow, cos LCD's don't work in extreme cold

You'll notice that an LCD screen's brightness will start to dim at 0C, with any touch screen functionality becoming increasingly unreliable, needing more direct, precise and heavier pressing to work as the temperature scales down to -20C.

You might think that using liner gloves with magnetic touch pads will do the trick, but most of the time they won't. It's not the gloves that's the problem, it's the screen.

Eventually, as it gets colder, your camera's LCD screen will become almost unreadable, unresponsive to touch, even with bare hands, then completely dead. The only solution is to warm up your camera by putting it in a ziplock bag (to avoid condensation) and place it under your clothing as close to your body as possible. This is why a nice set of baggy pants is very helpful.

The EVF of your mirrorless camera will work longer than your external screen due to internal heat generation caused by your camera's circuits grinding away, so a simple solution is to do all rear screen adjustments using your knobs and dials while looking through the viewfinder.

Finally, as the temperature drops to -50 and beyond, your camera will grind to a halt. Some camera models will continue to work down to -50, some will spit the dummy at -25C. Much will depend on camera brand and model, how the camera is being used and how much internal heat is being generated. As mentioned before, shooting video will warm things up, if only a little, allowing you to keep shooting those baby emperor penguin chicks.

At some point your auto focus lenses will also cease to work. Manual focus will keep you going, but it's not going to be fun or pretty.

Covering your equipment will help, but not much. Metal and plastic, so all your camera gear, are not effected by wind chill. But pure, brutal, extreme cold will get to them, eventually killing your best efforts.

Time to go warm up and try again later.

Of course all of the above is, as mentioned, much more difficult when out in extreme cold. Having the right clothing, footwear and glove system will go a long way to keeping you going. Our next article will cover that.

Amazon affiliate links:

Ugreen Cable: https://amzn.to/3TS7ho5

Nalgene Bottle: https://amzn.to/3TTMWPu

JJC Battery & Card Pouch: https://amzn.to/3RO2Esx

JJC Dual Battery Charger: https://amzn.to/48pRJMG

Anker PD Powerbank: https://amzn.to/3S9OWle

Toe Warmers: https://amzn.to/3RXOh5g

Rechargable Hand Warmers: https://amzn.to/3TSOb1d

Coleman 6-pack Cooler: https://amzn.to/3NS2XkQ

Alvin's Cables Dummy Battery: https://amzn.to/4dj8hsJ

Here it comes. Are you ready?